About the report and survey

This report is based on a survey of 506 literacy teachers in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland carried out online between late January and early March 2014. Just under two-thirds of those who participated were primary teachers, one-third were secondary teachers and 3% were special school teachers.

The report was written and produced for ReadingWise by JS Media Services

Foreword

Victor Lyons, Founder of ReadingWise & Tara Akshar

Welcome to this report which explores the views of English co-ordinators and literacy teachers in British schools about the most effective methods of teaching children to read. There is no more important subject. Literacy provides the key to success for children and adults, not only in the UK but all over the world. It is a subject close to my heart. ReadingWise UK actually began life in India in 2006. Known by its Hindi name of Tara Akshar, it quickly became the country’s most successful literacy programme.

Today, over 2.3 million women in India - many of whom had never been to school - have been taught to read and write and the programme has 300 learning centres across the country. It receives funding from the UK, Canadian, Swiss, and Indian governments, along with Microsoft, Oxfam, and Read India.

With this successful track record, the team behind Tara Akshar wondered if they could bring the programme to the UK. Would we be able to use some of what we learned in India to help the estimated one in five children who struggle with some aspects of literacy here in Britain?

Although we knew Tara Akshar worked, we wanted to make sure we could prove that ReadingWise, the English version, would be just as effective at teaching UK children who struggle with reading. So the programme was put through its paces by researchers from the University of Nottingham, Queen Mary University London, and the Royal Institution of Great Britain in a randomised control trial.

They found that ReadingWise raised reading ages for those in the bottom 20% of attainment by an average of 9.7 months in just 20 hours.

This report, based on a survey of 506 educators who teach literacy in primary and secondary schools, gives a clear picture of what the profession thinks works best when it comes to teaching children to read - and what doesn’t work so well. It shows, for example, that while synthetic phonics is valued as an important tool by practitioners it should not always be used as the main approach - especially for children with dyslexia and other disabilities and for the most able readers.

The clear message is that teachers need to be able to draw from a range of strategies and tailor their approach to suit the needs of individual children. They also underline the importance of making learning to read a pleasurable experience. ReadingWise English does precisely these things, with five different modules that can be used in combination or separately. With lots of animated cartoons and quizzes and a strong accent on humour the programme is not only effective but pleasurable too. Enjoyment is the key.

Victor Lyons

Founder, ReadingWise

March 2014

Helping every child reach their potential

About ReadingWise

ReadingWise English is a literacy solution for the 20% who struggle to read. Using a range of educational and psychological techniques to significantly boost reading ages, the programme is suitable for children and adults and helps everyone from below-average readers to those with special educational needs. The programme has different modules which can be used individually or in conjunction.

ReadingWise uses research and evidence throughout its development, and over the last 18 months has been trialling its programme in randomised controlled trial with primary, secondary, and special schools in the UK. The results so far indicate a 9.7-month average increase in reading age in a 20-hour intervention.

The next steps for the organisation are to continue developing and testing the programme with the objective of producing a literacy intervention for the 20% who struggle.

1. Background and main findings of the survey

Enjoyment: the missing element in the government’s approach to reading

Background

No one disputes the importance of getting children off to a good start with reading. Teaching them to read well is the key to success not only in mastering English and writing but in other subjects too. Those who struggle with reading invariably struggle with the rest of their school work and fall increasingly behind as they progress through primary and secondary school. Many also develop behavioural problems and fall out of mainstream education, requiring costly interventions to try to get them back on track. There are also consequences for society and the economy as young people who struggle for literacy face a potential future in low-skilled employment or on benefits, are at higher risk of suffering from poor mental health and are more likely to fall into crime.

It is not surprising, therefore, that literacy has become a hot political issue. The school inspection service Ofsted, in its 2012 report, Moving English Forward, pointed out that while attainment in English had risen in secondary schools since 2008, it had stalled in primary schools where far too many children had failed to reach the expected levels in reading and writing. One in five primary pupils failed to achieve the expected level of English in their SATs at the end of key stage 2.

Attention to the country’s poor record in teaching its citizens to read and write came into even sharper focus with the publication of a major study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in October 2013 which showed that young adults aged 16 to 24 had one of the lowest rates for literacy in the developed world, with England ranked of 22nd out of 24 countries.

Concern about literacy levels has led consecutive governments to take action. One of the strong est policy interventions came when the last Labour government acted on the recommendation of Sir Jim Rose, chair of a major review of the national primary curriculum, that all children should be taught to read using ‘high-quality systemic phonics’, with synthetic phonics as the preferred method. This ‘phonics first’ principle has been embraced by the present coalition government which further strengthened the emphasis on phonics by introducing a phonics test at the end of Year 1 to check children’s reading progress in England. Ministers backed this up by promising to fund additional support for children who were struggling to read.

This political strategy has been reinforced by Ofsted whose Moving English Forward report called on schools to place a stronger emphasis on spelling and handwriting and give pupils more encouragement to read for pleasure.

The survey

This survey of 506 literacy teachers was designed to find out what practitioners responsible for teaching literacy in primary and secondary schools think about these developments. It raises important questions about the apparent conflict between the government’s emphasis on synthetic phonics and the profession’s belief that children should be encouraged to read for pleasure. As the survey shows, while teachers regard phonics as an effective strategy for most readers many do not think it is effective for certain children, especially those with dyslexia and other specific learning disabilities. Many also do not think it is effective for the most able readers. Teachers would prefer to have the freedom to employ a range of strategies tailored to the needs of individual children.

The survey shows many literacy teachers believe too much emphasis on phonics is killing enjoyment of reading for many children. In light of this, it may be time for the government and schools to consider a more balanced approach allowing teachers greater flexibility and encouraging reading for pleasure.

Key findings of the survey

- More literacy teachers stress the importance of reading for pleasure (98%) and giving children the experience of a wide range of texts (92%) than on synthetic phonics (79%)

- Only one in five teachers (20%) fully supports the phonics test introduced in 2012 to check the reading levels of six-year-olds

- Less than one in four teachers (21%) fully supports the emphasis on synthetic phonics as the principle strategy for teaching children to read

- More than half of teachers (52%) think the current emphasis on synthetic phonics is either ineffective or not very effective as a strategy for helping children with dyslexia.

- Nearly half (45%) also think it is ineffective or not very effective at helping the most able readers while more than a third (37%) question its effectiveness for readers with learning disabilities

- Despite serious doubts about the policy, however, most teachers (58%) say their schools have increased the emphasis on synthetic phonics as a result of government guidance and many report a measurable improvement in children’s reading ability as a result

Summary of findings

Part 1: Support for testing and other initiatives

Testing at seven and 14

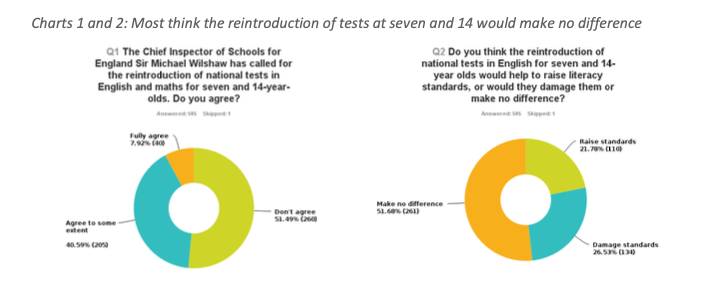

Less than one in ten teachers (8%) fully support Chief Inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw’s call for the reintroduction of national tests at the end of key stages 1 and 3. More than three-quarters (78%)four think it would make no difference or damage literacy standards (page 8).

Spelling and handwriting

More than four out of five teachers (84%) agree or partially agree with the Chief Inspector’s view that a stronger emphasis should be placed on spelling and handwriting (page 8).

English in primary schools

Almost half of teachers (47%) fully support the idea of employing more primary specialist English teachers while one in eight (12%) disagree. There is overwhelming support for Ofsted’s call for extra support and training to help primary English coordinators improve their subject knowledge.

Reliability of key stage 2 English tests

More than half of secondary English teachers (51%) believe tests taken at the end of primary school are unreliable as a guide to pupils’ reading levels. Only one in ten think they are reliable.

Part 2: Support for synthetic phonics and other reading strategies

Importance of different approaches

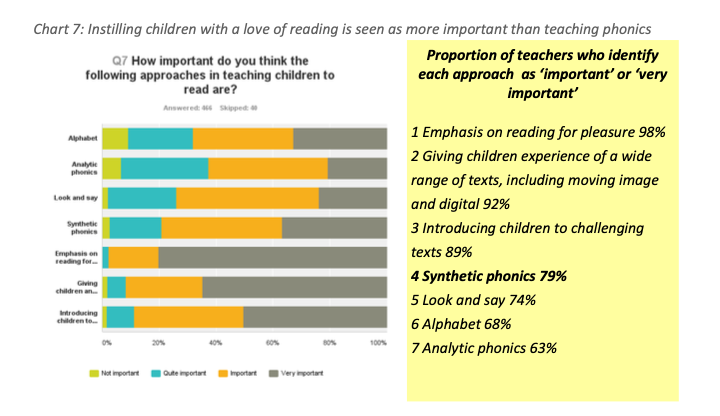

Eight out of ten teachers think it is important to use synthetic phonics to teach reading but nearly all teachers believe encouraging children to read for pleasure is even more important.

Phonics test for six-year-olds

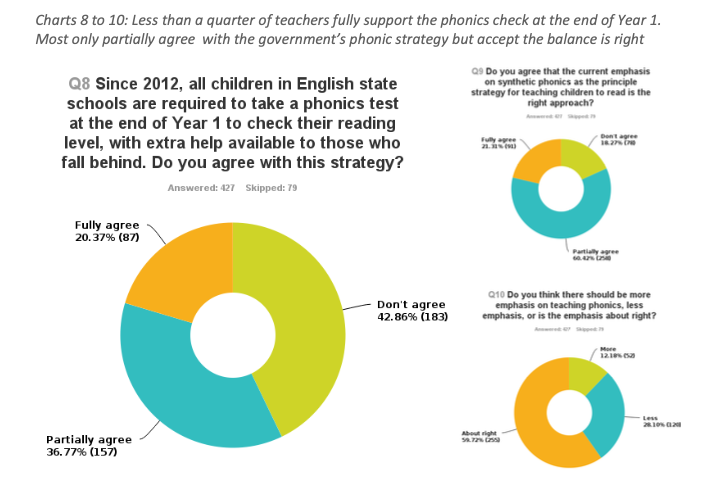

More than four in ten teachers disagree with the government's decision to give children a phonics test at the end of Year 1 to check their reading levels. Less than a quarter are fully supportive.

Government emphasis on synthetic phonics

Less than a quarter of teachers fully support the Government’s emphasis on using synthetic phonics as the principle strategy for teaching children to read. Two out of ten disagree while the rest partially agree. Despite the lack of enthusiasm for the policy, most think the emphasis is about right.

Effectiveness of synthetic phonics for different groups of readers

More than eight out of ten teachers (81%) think synthetic phonics is effective for teaching average readers but less than half (48%) think it is effective for teaching children with dyslexia. Fewer than six out of ten (55%) think it is effective for teaching the most able readers.

Impact of the government’s phonics strategy

More than half of teachers say their schools have increased the emphasis on phonics in the light of government guidance. Four out of ten of those whose schools have increased the emphasis on phonics report an improvement in pupils’ reading ability.

Additional support for struggling readers

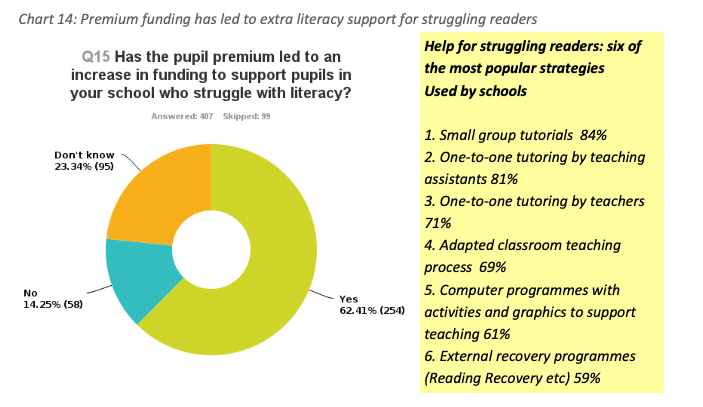

Small group tutorials and one-to-one tutoring are the most common forms of additional help given to struggling readers to help them catch up.

The pupil premium

Six out of ten teachers say the pupil premium has led to an increase in funding to support pupils who struggle with literacy.

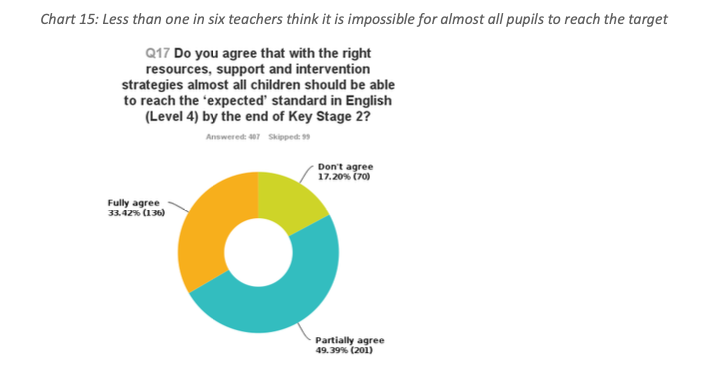

Part 3: Ten strategies to achieve world-class literacy levels

More than eight out of ten teachers agree or partially agree that with the right resources, support, and intervention strategies almost all children are capable of reaching level 4 in English at the end of their primary education. In order to achieve this world-class standard of literacy teachers identified ten principle strategies. They are:

What teachers would like to see: 10 strategies to achieve world-class literacy

1. Consistently good teaching

2. An English specialist for every primary school

3. Early intervention to support struggling readers

4. Tailoring reading strategies to fit the individual child

5. Encouraging parents to read to their children

6. Early childhood support to introduce children to books, stories, and nursery rhymes

7. Encouraging children to read for pleasure

8. Starting the formal teaching of reading later

9. Making creative use of technology

10. Trusting teachers

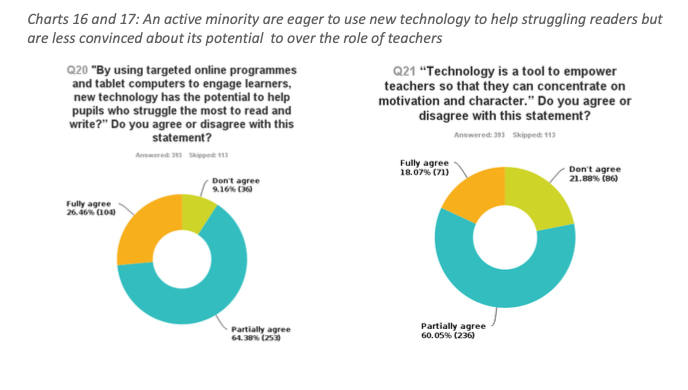

Part 4: Digital technology and literacy resources

Potential of new technology to engage struggling readers

An active minority of teachers - one in four - think that using targeted online programmes and tablet computer technology has the potential to help pupils who struggle the most to read. One in ten teachers disagrees while the rest partially agree.

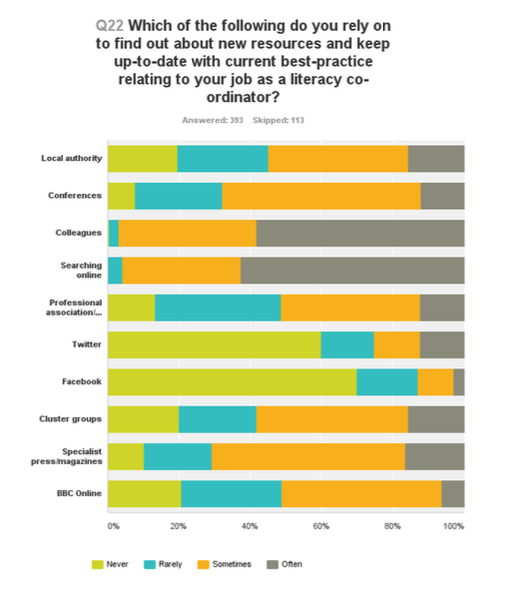

Keeping up with best practices and new resources

Searching online is now the most commonly used method of keeping up-to-date with best practices in literacy teaching and finding out about new resources (page 19).

Support for testing and other initiatives

Testing at seven and 14

Launching his annual report in December 2013, the Chief Inspector of Schools Sir Michael Wilshaw urged the government to reintroduce formal tests in English and mathematics for seven and 14-year-olds. Sir Michael argued the tests, abolished by the last Labour government, were a way of measuring children’s progress.

"If we are serious about raising standards and catching up with the best in the world, we need to know how pupils are doing at seven, 11, 14 and 16," he said.

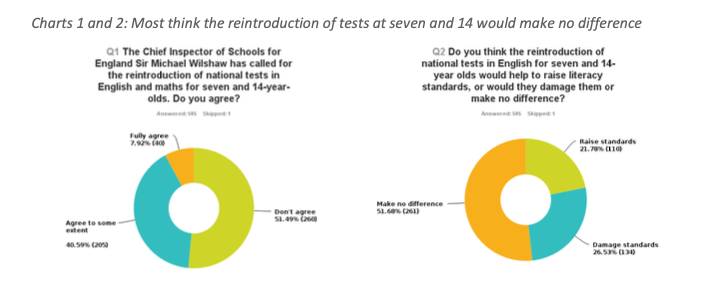

But there is little enthusiasm from literacy teachers for the Chief Inspector’s initiative. Less than one in ten fully supports the idea while half are opposed (Chart 1). Opposition among primary teachers is significantly stronger with well over half (59%) against compared with 42% of secondary teachers.

Asked whether the reintroduction of national tests for seven and 14-year-olds would help to raise literacy standards three-quarters believed it would make no difference or even damage standards of literacy. Less than one in four teachers believed it would raise standards (Chart 2). Once again, opposition was higher among primary teachers with more than a third (35%) saying it would damage standards.

Charts 1 and 2: Most think the reintroduction of tests at seven and 14 would make no difference

Spelling and handwriting

In his annual report (2012-13) the Chief Inspector also said a stronger emphasis needed to be placed on spelling and handwriting and there was broad support for this from both primary and secondary teachers. More than four out of five fully or partially agreed while 17% disagreed (Chart 3).

Specialist English teachers in primary schools

The inspection service Ofsted would also like to see greater specialist input and improved subject knowledge when it comes to teaching English in primary schools. In its 2012 report Moving Forward it said the government should provide support to increase the number of specialist English teachers at primary level. It also said support and training should be given to improve the subject knowledge of existing English coordinators in primary schools.

There is general backing for the idea of boosting the number of specialist English teachers in primaries, although support from primary teachers is significantly less than from secondary teachers, reflecting the different traditions of the two sectors. Overall, almost half of teachers surveyed fully supported the idea (47%) while almost one in eight (12%) disagreed (Chart 4). Among primary teachers, however, the proportion in full agreement fell to just over a third (37%), perhaps reflecting the strong tradition for generalist teaching in the sector.

There is overwhelming backing, however, for Ofsted’s call for extra support and training to be provided to improve the subject knowledge of existing primary school English coordinators. Nearly six out of ten teachers in the survey were in full agreement with less than one in 20 against (Chart 5). Once again, rather fewer primary teachers were in full agreement with the proposal - just over half compared with two-thirds of secondary teachers – but only 6% disagreed.

Charts 3 to 6: Ofsted initiatives to raise English standards are welcome but many secondary teachers think the key stage 2 English test is an unreliable guide to children’s reading levels

Reliability of key stage 2 English tests as a guide to reading levels

The survey reveals widespread skepticism among secondary English teachers about the reliability of key stage 2 tests as a measure of children’s reading levels. More than half said they thought the tests taken at the end of primary school were unreliable as a guide to the reading levels of children newly arrived in Year 7. Tellingly, only one in ten (11%) thought the English tests were either quite reliable or very reliable (Chart 6).

3. Support for phonics and other reading strategies

Importance of different approaches

There has been consistent pressure from political parties in recent years for teachers to employ synthetic phonics as the principle strategy for teaching children to read. This ‘phonics first’ principle was introduced by the last Labour government and has been enthusiastically embraced by the present Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition.

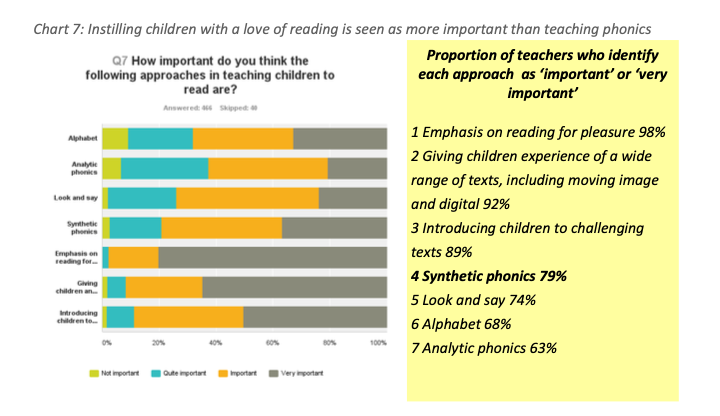

While teachers who took part in the Reading Wise survey generally agree synthetic phonics is important as a tool for teaching children to read they clearly believe other approaches are even more important. Overwhelmingly, they think the emphasis should be on encouraging children to read for pleasure and giving them experience of a wide range of texts, using moving images and digital resources as well as books. While eight in ten teachers (79%) think using synthetic phonics is important they place it fourth in order of priority behind other strategies (Chart 7 and box).

Chart 7: Instilling children with a love of reading is seen as more important than teaching phonics

Phonics test for six-year-olds

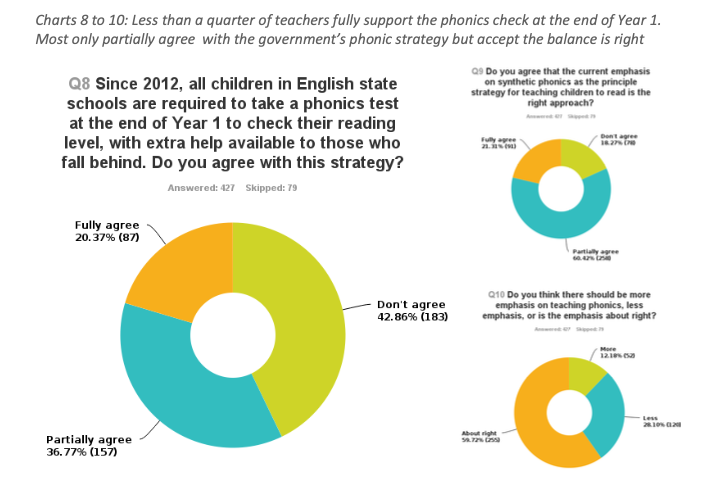

In 2012, the Government introduced a phonics test to check children’s reading levels at the end of Year 1. The strategy, which includes extra help for children who fall behind in their reading, is proving to be unpopular with many teachers.

Only two in ten (20%) of those surveyed fully support the strategy, while more than four out of ten (43%) disagree (Chart 8). Among primary teachers, opposition is greater still with over half (54%) disagreeing with the strategy. Only 12% fully support it.

Government emphasis on synthetic phonics

Less than a quarter of teachers (21%) fully support the current emphasis by education ministers on synthetic phonics as the principle strategy for teaching children to read. Most only partially agree with the policy (60%) while almost one in five (18%) is opposed (Chart 9). The figures indicate that teachers are at best lukewarm about the policy.

However, when asked whether more or less emphasis should be placed on phonics a clear majority (60%) said the emphasis was about right. Even so, almost three out of ten teachers (28%) believed there should be less emphasis on teaching phonics while only one in eight (12%)thought there should be more emphasis (Chart 10).

Charts 8 to 10: Less than a quarter of teachers fully support the phonics check at the end of Year 1. Most only partially agree with the government’s phonic strategy but accept the balance is right

Effectiveness of synthetic phonics for different groups of readers

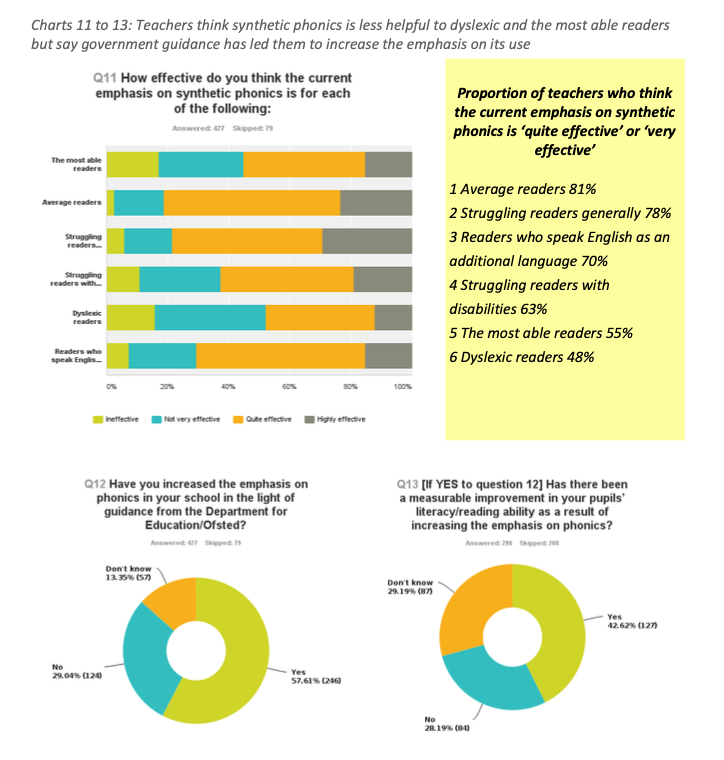

What seems clear from the survey is that while most teachers recognise the importance of synthetic phonics in teaching children to read they see it as just one of a number of important strategies (as Chart 7 demonstrates). The reason for their scepticism becomes clear when they are probed about the effectiveness of synthetic phonics as an approach to teaching children of different abilities.

Chart 11 shows that while teachers believe synthetic phonics is either ‘effective’ or ‘very effective’ as a method for teaching average and struggling readers generally (81% and 78% respectively think this) they believe it is far less effective for certain other groups of children. Less than six out of ten (55%) think it is effective or very effective for teaching the most able readers.

Even more striking is the fact that less than half of the teachers surveyed (48%) think the current emphasis on synthetic phonics is effective or very effective as a strategy for helping children with dyslexia to read. Most (52%) think it is either ‘ineffective’ or ‘not very effective’.

A substantial minority also believe the strategy is either ineffective or not very effective for teaching reading to children with other learning disabilities (37% think this). The table below (page 11) shows how teachers rate the effectiveness of the strategy for different groups of readers in rank order.

Impact of the government’s phonics policy

Despite professional doubts about the efficacy of synthetic phonics as a blanket strategy, a clear majority of teachers (57%) say their schools have increased the emphasis on phonics in the light of guidance from the Department for Education and Ofsted (Chart 12). The finding suggests the government has succeeded in increasing the emphasis on synthetic phonics in the classroom.

Also positive for the government is that more than four out of ten teachers (42%) who report an increase in the teaching of phonics in their schools say there has been a measurable improvement in pupils’ reading ability. This compares with 28 percent who say there has been no improvement (Chart 13).

Charts 11 to 13: Teachers think synthetic phonics is less helpful to dyslexic and the most able readers but say government guidance has led them to increase the emphasis on its use

The proportion of teachers who think the current emphasis on synthetic phonics is ‘quite effective’ or ‘very effective’

Additional support for struggling readers

Teachers were asked which of a number of approaches to help struggling readers they had employed in their schools. The most common (see table) were additional teaching support delivered in small groups or one-to-one. Teaching assistants were rather more likely to be used than teachers for one-to-one tutorials.

Many teachers also reported that their schools had adapted their classroom practice, with teachers changing the way they teach in order to help struggling readers. The table below lists these approaches in order of popularity.

Chart 14: Premium funding has led to extra literacy support for struggling readers

Help for struggling readers: six of the most popular strategies Used by schools

1. Small group tutorials 84%

2. One-to-one tutoring by teaching assistants 81%

3. One-to-one tutoring by teachers 71%

4. Adapted classroom teaching process 69%

5. Computer programmes with activities and graphics to support teaching 61%

6. External recovery programmes (Reading Recovery etc) 59%

The pupil premium

Most teachers in the survey take a positive view of the pupil premium, the policy introduced by the Government in April 2011 to provide schools with extra funding to help children from low-income families.

The policy has brought clear benefits for struggling readers, according to the survey. A sizeable majority of teachers surveyed (62%) said the premium had led to an increase in funding to support pupils who struggle with reading. Only 14% said there had been no increase (Chart 14).

4. Ten strategies to achieve world-class literacy levels

What would it take for almost all pupils to achieve a good standard of reading and writing?

When the national assessment system was introduced in England in the late 1980s it was envisaged pupils of average ability and above would reach level 4 in English by the age of 11. The introduction of school league tables in the early 1990s quickly changed the way SATs were perceived, however, level 4 became the benchmark all pupils were expected to achieve.

We wanted to discover whether teachers believe this expectation is realistic given the right conditions. Asked whether they thought that with the right resources, support, and intervention strategies almost all children should be able to reach the ‘expected’ standard by the end of primary school only one in six teachers (17%) disagreed. Almost twice as many teachers (33%) fully agreed while the rest (49%) partially agreed (Chart 15).

Chart 15: Less than one in six teachers think it is impossible for almost all pupils to reach the target

This suggests teachers are mainly positive about the possibility of nearly all pupils reaching level 4 in English by the age of 11 given the right circumstances. But they are also realistic about what can be achieved under current circumstances.

To discover more about their views, we asked teachers what they believed would be needed to enable virtually all children to achieve standards of reading and writing that they would associate with a world-class education system. From the hundreds of comments we received several clear themes emerged. One woman primary teacher in Hampshire succinctly summed up the conditions many teachers believe would be required: “Time, money, consistency, and all teachers believing that it is possible.”

Teachers generally agree that in order to achieve ‘world-class’ literacy standards schools require more resources and less government prescription. They would like to be given the discretion to use a range of different strategies to meet children’s individual needs rather than having a single, one-size-fits-all strategy imposed on them.

Nikki Morgan, the headteacher of Holy Trinity Primary School in the London borough of Merton, listed the following necessary conditions: “Slightly smaller class sizes, less top-down directives from the Department for Education, and more autonomy for schools. Recognition that all children do not learn in the same way and so schools should be encouraged to be creative and try different methods and resources which have been tried and tested.”

Anthony Kern, headteacher at Gosfield Primary School in Essex, expanded on this theme. “Education strategy needs to be taken out of the political arena and for highly effective leaders and managers to drive education practice,” he said.

“Children should start school later and parents should be encouraged to work with their children at home giving them rich experiences based on a wide range of reading texts. Library strategies need to reflect the importance we place on reading and literature and more money is needed for schools to spend improving literacy provision.”

State schools also needed to be better funded if they were to compete with the independent sector, he said: “Private schools do better generally because of the money they have to spend on resources, not the background of the parents.

We have a budget of £250,000 a year for 140 children - £1 700 per pupil. In the private school on the same road, they have £10,000 per pupil. We get better results in both key stages: imagine what we could do with even double the budget we have.”

10 strategies to achieve world-class levels of reading and writing

From the hundreds of comments received from teachers who took part in the survey, it is possible to identify ten common strategies for raising reading and writing fluency to create world-class literacy standards.

These are set out below, with supporting quotes from teachers:

1 Consistently good teaching supported by high-quality support staff, initial teacher training, and continuing professional development

“Consistently good teaching in all classrooms, which would have an impact upon teacher training, recruitment, and procedures for capability. No child should have anything less than a good teacher.” Amanda McGarrigle, primary headteacher, Kent

“Enthusiastic and highly skilled teachers who use a range of teaching techniques adapted to the individual needs of their pupils.”

Secondary teacher, South East

2. A specialist for every primary school – all primaries should have either a specialist English teacher or the support of a local literacy adviser

“More specialist teachers and the funding to allow them to work, on a daily basis, with those children who need the support.”

Liz Marshall, primary teacher, Kirklees

“Employ local expert literacy teachers and send them in as advisers to schools that need them.” Primary headteacher, Cheshire

3. Early intervention – struggling readers need to be identified and supported early on

“Early detection of difficulties (trained experts to help evaluate the specific difficulties encountered by individual students). Early intervention where a great relationship between student and teacher is seen as essential to allow the best chance of achievement.”

Val Lamont, primary teacher, South East

“Early identification and intervention. Focus on key reading and writing skills so that the primary curriculum allows time for repetition and reinforcement of key skills rather than the need to keep moving children onto the next stage of the very challenging curriculum primaries face now.” Primary teacher, England

4. Tailor strategies to fit the individual child – reliance on synthetic phonics isn’t always enough and different children need varied support through targeted interventions

“Teaching strategies should be tailored to the individual rather than enforcing all to participate in strategies which do not help (synthetic phonics).”

Sarah Haley, primary teacher, London borough of Southwark

“Teachers empowered to teach in the ways that best suit their students' needs, rather than an imposed one-size-fits-all system. An increase in resources to allow more focussed small-group or individual teaching for struggling readers/writers.”

Secondary teacher, Derbyshire

5. Reading at home – parents should be encouraged to read with their children and support their learning

“There are always going to be children who struggle with reading; we cannot do it all in school. Parents also have a responsibility to help their children learn to read. All parents supporting their children to read and write at home would, I believe, have the greatest impact on their learning.” Jo Blakeman, primary teacher, Wiltshire

“The system should begin from birth - babies and small children being read to by their parents and enjoying the process. This then aids the process when they reach school age.” Secondary teacher, Staffordshire

6. Effective early childhood development – children and families should be given support from birth onward by introducing them to books, stories, and nursery rhymes

“Parental involvement, particularly in early years. When babies go to GP clinics perhaps advice should be given to parents about books, looking at them, playing with them, getting used to handling and seeing books.” Suzanne Parker, secondary teacher, Manchester

“Support for 'problem families' before children begin school. Many who struggle enter school with limited language, and no knowledge of books, rhymes, fairy stories etc. They don't even speak in sentences so how can they learn to write them.” Kim Champion, primary teacher, Nottinghamshire

7. Encourage reading for pleasure by giving children access to a wide range of books, listening to stories in shared reading sessions, and reading aloud

“Emphasis on reading for pleasure, a wider range of texts available in classes and schools, reading corners, timetabled 'enjoyment of reading' sessions.” Sarah Hughes, primary teacher, Wolverhampton

“A determined focus on reading for pleasure. For struggling readers, we need to teach them memory skills, rather than give them endless drills in dreary phonics or with word-recognition flashcards. Memory work, using pleasurable and meaningful texts produces true fluency very quickly, without the frustration pupils experience with phonic/flashcard approaches.”

Martin Malcolm, primary supply teacher, London

8. Start the formal teaching of reading later when children are ready

“Starting formal teaching for children at a later age. More enjoyment of stories and drama in F1, F2, and Year 1. Other countries don't force formal teaching until the age of 6-plus and seem to achieve better than us.” Primary teacher, Derby

“Children must not be forced to read before they are ready. We should look to the Scandinavian systems and their success when children are not taught formally until they are seven.” Secondary teacher, Cheshire

9. Make creative use of technology to increase interactivity in the classroom

“Creating lessons with more interactivity and physical dynamism to cater for students whose first instinct is not to sit down with a text and enjoy it, and employ the use of technology that kids use every day - for example, computers, phones etc.” Cassandra Jolly, special school teacher, Devon

“Quality first teaching, with high-quality multisensory resources. A mixture of phonics, reading for pleasure, and comprehension work.” Primary teacher, Norfolk

10. Trust teachers to deliver – reduce the amount of testing and paperwork and give professionals time and space (and the resources) to teach literacy effectively

“Undertake good research, make this available to teachers, and then leave teachers to teach in the way they think right for the child.”

Primary teacher, Hertfordshire

“Enjoyment, enthusiasm, more learning freedom, less tests!” Primary teacher, Lincolnshire

“Less pressure on schools to achieve uncontainable targets. Children who fall behind by year 6 are cast aside in the drive to push pupils who are nearly at level 4. Those still at level 2 for example receive no or little support as they won't help the school's statistics!” Primary teacher, Leicestershire

“For education to be taken out of the political arena so that there isn't a major change every time there is a new government. As it stands nothing is kept in place long enough to actually have an effect on the children's learning. Also, there needs to be an understanding that children come from very different backgrounds, and as such the curriculum within that school should reflect and adapt to their needs.” Primary teacher, Birmingham

“A world-class education system would come from consistency and not implementing new policies and strategies all the time - this makes teaching very difficult and impacts pupils' learning. A more consistent and national approach to planning and subject coverage would guide those teachers who are struggling, and ensure that all pupils are getting a consistent education across the board. If reading, writing, and maths are to be the primary focus in Primary education, there should be less to 'cover' in foundation subjects to allow teachers to concentrate on the core subjects. Secondary teacher, England

5. Digital technology and literacy resources

Potential of new technology to engage struggling readers

The development of touch-screen technology over the last decade has opened up the prospect of a revolution in teaching and learning. Tablet computers and other mobile devices are increasingly being used in the classroom providing children and teachers easy access to a rapidly growing numberof online resources. Many schools have embraced new technology to engage children excitingly and creatively of learning.

We asked teachers who took part in the survey whether they thought that, by using targeted online programmes and tablet computers to engage learners, new technology had the potential to help pupils who struggle the most to read and write. More than a quarter fully agreed (26%), while less than one in ten (9%) disagreed (Chart 16).

This picture shows that an active minority of teachers are eager to seize the potential of digital technology to help struggling readers. A much bigger group, almost two-thirds (64%), partially agree that technology has the potential to engage struggling readers but are not yet fully convinced.

There is more scepticism when it comes to supporting the view of Matthew Hancock, the skills and enterprise minister, who told the Sunday Times in December that developments in new technology meant computers would in the future take the lead in imparting knowledge while teachers focused on mentoring, coaching, and teaching.

Asked whether they supported the minister’s statement that, “Technology is a tool to empower teachers so that they can concentrate of motivation and character”, 22% disagreed while 18% fully agreed (Chart 17). Although the minister’s view is shared by leading technology entrepreneurs who see online lectures and programmes as a means of “flipping the classroom” – with teachers becoming mentors and coaches while pupils do much of their learning online – there is clearly some way to go before the profession is fully convinced.

Charts 16 and 17: An active minority are eager to use new technology to help struggling readers but are less convinced about its potential to over the role of teachers

Keeping up-to-date with best practices and new resources

Searching online is now the first port of call for almost all teachers seeking to find out about new resources and keep up-to-date with current best practices relating to literacy.

When asked which sources they relied on most frequently to keep abreast of things, searching online came top (64% did so often), while colleagues were also cited as an important source (57%). These were used far more frequently than any other sources although specialist publications, conferences, cluster groups, the local authority, professional associations and the BBC website were all seen as useful. A majority of teachers said they relied on these sources often or sometimes (Chart 18).

Social media is relied on by only a relatively small proportion of literacy teachers. Of the two biggest social media platforms, Twitter is used far more than its rival Facebook, perhaps because of its emphasis on news, information, and website links. Nearly a quarter of teachers (22%) said they relied on Twitter often or sometimes, compared to one in ten (10%) on Facebook.

Chart 18: The Web is now teachers’ principle source for finding new literacy resources

ReadingWise in the Classroom

Since this pilot RCT study, ReadingWise has helped over 100,000 pupils in primary and secondary school advance their reading abilities, fluency, and enjoyment of reading.

Read our other studies:

University of Cambridge, Reading More Wisely

"Reading Wise has been great for our school. It was recommended to us from a cluster school and what a difference it has made in such a short time! We have used Reading Wise as a targeted intervention for 10 children as a trial and have been blown away by the results.”

“In only one term, the majority of our children made at least 10 months of progress in their reading age- some even more! We have decided to purchase Reading Wise for the whole school and are very excited to see the progress throughout the school.”

We are extremely impressed with the impact Reading Wise has had in our school and are very excited to continue our journey. I would recommend Reading Wise to any school!"

Hannah Boardman, Irlam Primary School, Salford, UK

See what other headteachers and literacy leads say about ReadingWise in our case studies and frequently updated testimonials.

Boost your school's literacy results: Arrange your 20-minute demo at a time to suit you.

We highly recommend you spend 20-minutes running through the programme with our friendly and knowledgeable team by booking a demo to suit your diary